Democratization won’t save research

It is a band-aid for a deeper problem

RESEARCH

12/12/202312 min read

Democratizing research is still a debated topic at the moment. There doesn’t seem to be a clear answer about whether or not it should be done, and from what I can tell, that’s because people are having different arguments on top of each other. Simplifying the argument into the Yays and the Nays, the discussion is oddly skewed. People against democratization say it’s too much time and effort that doesn’t produce much value, but a good amount of harm. Interestingly, even those in favor admit the possible dangers but say that the value to the practice and the organization outweighs them. The stakes of this argument have gotten higher given recent global industry and technological shifts, so I wanted to disentangle the different arguments to get a bit of clarity.

Generally, the disagreements about democratization seem to come from two sources:

How people explicitly or implicitly define the term “democratization”

What problem democratization is being used to solve

Let’s break them down.

What the heck is research democratization?

If you are a researcher at an organization or you work with or around some of them, you’re probably familiar with the concept of democratization. In a nutshell, it involves a researcher or research team teaching non-researchers (designers, product managers, engineers, etc.) to do some researchy things. These partners will get anything from guides and templates to more direct guidance including crash courses and workshops so that they can do things that a researcher would normally be responsible for, with varying degrees of competency.

The differences in how people define “democratization” boils down to a few things:

What types of research are democratized? (Formative? Generative? Evaluative?)

What phase of the research process are non-researchers involved in? (Planning? Building? Data collection? Analysis and synthesis? Reporting?)

How much of the research process is done ONLY by non-researchers, without a researcher involved? (Different setups can range from a close partnership to the non-researchers tackling research solo)

You can visualize it as a spectrum from no democratization at all, to whatever it means to “fully” democratize a job function.

Why give away your job?

There must be a good reason that people — smarter than you and I — think that it’s a good idea to have people do work they’re not well-trained for. The origin of the democratization conversation is pretty similar across all organizations that have an R&D function: More resources and staffing are allocated for the D than the R, and researchers don’t have enough bandwidth to do all the things asked of them, thus becoming a bottleneck for other work.

At any large company that produces a product or service, ratios of researchers to designers or engineers are often in the 1:15 to 1:5 range at best (Kelsey Kingman cites a 1:8 ratio at Fidelity), with the larger tech companies usually staffing more researchers (The layoffs from 2022 and 2023 have likely made these ratios more unfavorable). It is not unheard of to be the only researcher at a small to medium-sized company. The reason that research teams are so thin is that one “unit” of research tends to support, inform, and enable a broader swath of other work.

Because research is cool like that.

The problem is, organizations sometimes have a difficult time understanding just exactly how many “units” of research are needed to accomplish what they want to do, and doing what businesses do naturally, they will hire the minimum they think is needed. The result is that researchers are regularly faced with a reality that every working professional experiences at some point in their careers: There is too much work to do and too little time.

This is the moment when the decision usually happens. The most straightforward options that usually come to mind to address the bottleneck are:

Say “no” to the work, risking alienating partners and inviting rogue researchers who do research on their own without anyone else knowing

Say “yes” to the work, overloading the research team even more, straining team morale, and risking burnout and costly mistakes

Democratize the work, offloading the work onto the people asking for research, empowering them to move forward without as much effort from researchers

It’s not hard to understand why the idea of democratization is attractive. On its surface, it seems like it could be an “everybody wins” scenario. In some cases, it gets close…

Well-executed democratization done for the right reasons is a no-brainer

One approach to democratization is essentially a structured form of cross-team collaboration, bringing stakeholders along for the research ride and ensuring that the results are broadcast outside the immediate team for maximum reach. These processes are set up in order to ensure that research is relevant to stakeholders’ needs, that stakeholders and partners feel ownership over the work, and to get more support for doing the work itself.

Basically, this approach seeks to maximize the research impact, not to lighten the load. Researchers are still in charge of either executing or reviewing the work at every stage, but non-research partners get a “behind the curtain” look at how the sausage is made.

At the cost of more time and effort to accommodate a bigger working team, “collaborative democratization” has enough benefits that it’s a relatively common practice.

More research gets done than it would without stakeholder involvement

Greater impact: With more stakeholders involved in research from the planning to analysis phases, the results can be more relevant and valuable to the organization

Upskill partners: Stakeholders get a better understanding of the research process and where insights come from and can grow more skillful at asking good questions

Recognition: More involvement of different parts of the organization in research means more visibility of research to the organization

Avoiding the extremes of democratization

We’ve reached the end of the helpful parts of democratization, which falls somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. The endpoints are obviously not feasible, and possibly imaginary. I am not aware of any researchers in an organization who either do all the research in a silo without involving anyone else, nor have I met any researchers who are living the easy life because they have given away their job entirely (If you know any, please introduce me). However, I want to emphasize the risks of what I will call “extreme democratization” which involves stakeholders taking on part of the research process without any guidance or oversight from the research team. Want me to do research? I won’t do it for you, but I will teach you how to do it yourself without waiting for me.

It’s the corporate version of teaching others to fish, which is problematic when your job is to be the fisherman.

Giving up too much control over research comes at a cost:

Continuous investment: Even the laziest researchers won’t just tell someone else to do their job with no guidance. Teaching others to do something new requires a lot of time and effort and must be done repeatedly

Lower quality: Research done by people who are not researchers is going to be worse than if a professional researcher did it; mistakes are guaranteed and can lead to confusion, bad decisions, and even legal problems. One counterpoint is that “research” will be done by non-researchers no matter what, so there is an argument for making people better at it instead of trying to prevent them from doing it

Unwillingness: Non-researchers have their own work to do, and might not want the extra job added to their busy schedules

Career risk: Giving others the responsibility to do your job communicates at some level that you are replaceable by a mostly untrained human (or an AI)

Democratization often misses the point

Extreme democratization (giving away full control of part of your job) is clearly not a good idea, but even collaborative democratization is questionable when it is used as a tool to solve for lack of bandwidth. Even in the perfect world (where the costs of democratizing are smaller than the costs of doing the work yourself), democratization only addresses the surface issue, not the root causes behind the lack of resources dedicated to research. Here are a couple of very real contributors to that universal problem:

No one understands the process or purpose of research: There is no clear process for doing research at your organization so it defaults to a service model where people ask for what research they think they need, for the purpose of validating what they already want to do.

Researchers aren’t well-organized: Research says yes to too much work partially due to a lack of good project management. If it’s not clear how much time and effort things take, and it’s also not clear what’s the most important thing, how can you ever justify saying no to anything?

Researchers forget what they are paid for: Research doesn’t effectively communicate its impact on the organization. Data, insights, and recommendations are the direct outputs of the work, and reports serve to document those. But nobody gets money to grow a team because of how many reports they publish. They get funding because of how much value they brought to the business, however the business measures that. Money is usually a good starting point, but it’s not the only factor.

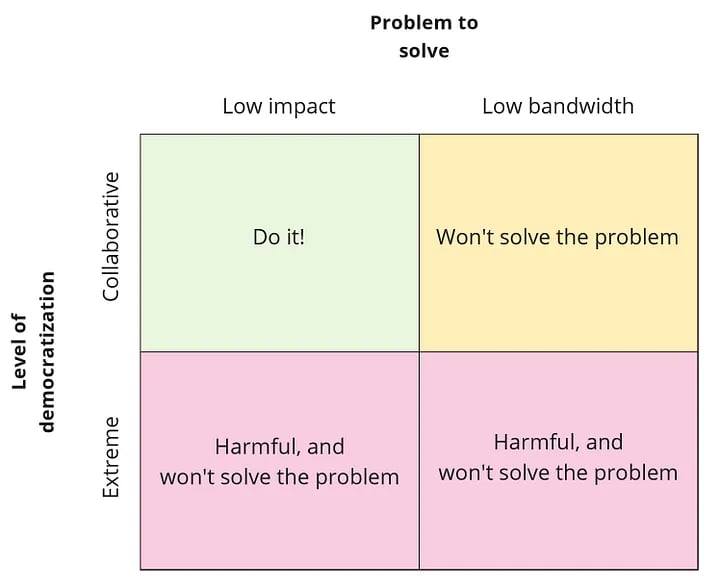

A quick summary before we get to the good stuff

In case you are looking for a “do I do it or not?” type of answer, here’s a handy diagram outlining my perspective:

tl;dr:

If you’re trying to improve your research impact, involve your partners and stakeholders! Just make sure it’s a collaboration and not a handoff

Don’t use democratization to solve a lack of bandwidth. Even if you do it well, you probably won’t save any time doing it

A better way to address low support and resources

Before you take the extremely long and painful route of convincing other people to do some of your job in your stead, try these much easier and more helpful things first. Even if you democratize later, these will help.

Document your process: Stop compromising as much on how others want you to work and take a stand about how you think you should work. Outline a clear process, what is flexible, and what is required (with justification). Without this, you will always be at the mercy of what other people want to do. You are an expert in your craft, and you should act like one.

Say no: to all but the most important things and the things that have the clearest value. Radical prioritization reduces your workload but makes sure the work you do is way more impactful. It also helps your partners know and express what is important to them.

Talk numbers: this means showing what value your work brought to the business. It’s not about reports made or insights delivered, it’s about decisions enabled, problems solved, and money made or saved. When your value is quantifiable, you can make the case to allocate more resources to multiply it.

If you choose to democratize, do it well

Well-managed democratization does add value, and a lot of the risks of sharing responsibilities can be avoidable. Here are some tips for keeping things relatively smooth. I recommend Christopher Nash’s article for a more thorough guide on how to democratize well.

Clarify everyone’s responsibilities: Who owns what process? How should people engage? Being clear about the rules makes it more likely that people will follow them and less likely that you get “rogue research.”

Teach, but be there to help: It took you years to learn what you know, and more years to get good at it. Giving people a 2-hour workshop and a 10-point checklist isn’t going to be enough, you must be available in some way to address questions and confusion, and just be a sounding board.

Be a polite but firm gatekeeper: Where are the checkpoints before things can move on? What is off-limits? Democratization should be an invitation to be involved, not a key to the city. Without guidelines and governance, data becomes cheap and messy, and you risk violating ethical best practices and even legal guidelines (a good example is data privacy laws). The less observable effects may include the question that may pop up in minds across your organization: “Why do we need you again?” You know that the work you do is valuable, but that isn’t enough.

It can be hard for a non-expert to tell good research from bad research. And it’s often non-researchers in control of the budget.

Keep in mind that even with the best intentions, your reality may look different and it may not be possible to do all of this in addition to your day job.

Isn’t gatekeeping bad?

Taking a slight detour, scientists borrowed the term “democratization” from the political sphere, and democracy is about representation and power. With research taking the role of discovering, curating, and sharing knowledge, failing to be inclusive and transparent with the research process and outputs also risks disempowering those who you are researching to some degree. Within an organization, this can translate to isolating the people you work with. However, even from this perspective, it is important to understand the nuance that a democratic process does not mean that decision-making power in all stages of research is shared.

I once worked with a talented designer who had been put into the position to carry out research with no guidance. He did it, and in his words, “didn’t know what he was doing.” He didn’t feel confident in the quality of the work or the findings. Yet, the work happened, but that’s not the end of the story. The research findings were used to make decisions for the immediate project, but were also passed around to other teams to inform their work and accepted as truth. By that point, the questionable work was out of his control.

I hope this example illustrates the point that democratization without guardrails is a recipe for potentially widespread harm in your organization, and is very difficult to trace and fix. By definition, other people’s jobs do not include doing yours. They are not contractually accountable for the work; you are. You are technically shirking your responsibilities by giving away full control over your job.

A moment of self-reflection for the industry

UX Research is a comparatively new function within organizations, even though its roots are older. In most industries, it’s also seen as a “non-critical” function; the concept of UX research is only a few decades old and companies did “fine” before that (not really, but perception matters). Most organizations are still struggling to understand the value of research. Some organizations and many people within organizations resist the practice as a whole: who are these people telling us what to do when we have our own great ideas? Why do we have to take the time to actually research when we could just make things? Is it better, faster, or even helpful to do research?

These doubts have always been there, even if it feels particularly salient at the moment. Although I don’t think the discipline is dying per se, some of our strategies have been unproductive.

Research tries too hard to please

Research as a practice often reacts to unfavorable conditions in what I would describe as a submissive pattern:

Say yes to all the demands, even the bad ones (to be a “good team player” and “build trust”)

Find ways to reduce the quality of the work to its bare bones to meet deadlines set by others (to be “efficient”)

Bend over backward and compromise about what work to do (to “show what we can do and get a seat at the table”)

Researchers in consultancies may feel forced to do some of these. After all, clients hold the power in this relationship. But for in-house researchers, all of these activities are undertaken with the mindset of “We’ll show them how awesome we are even with a fraction of our abilities!” The problem with this plan is that it often succeeds, but with results that weren’t part of the plan: what you just did is now the expectation.

The outcome of saying yes too much is that people assume your crazy contortions are your normal state, and those ideals you compromised on aren’t that important to you. And businesses push people to work better, faster, and with fewer resources than their normal state as a matter of principle so these strategies tend to backfire.

Democratization will not solve the big research problem

In the midst of an industry-wide panic about the future of UX research in organizations, people are suggesting all sorts of opinions on what should be done to avoid its downfall and there are people on both sides of most of these strategies. Democratization, specialization, integration with product, the list goes on. These strategies are aimed at what is perceived to be the problem, which ranges from long-existing problems like a lack of research bandwidth and support, to more recent developments like mass layoffs and the rapid deployment of AI.

Whatever the specific problem is, the big fear seems to be that organizations don’t value having researchers do research. Whether the fear is being replaced by non-researchers, junior researchers, digital researchers, or just skipped over altogether as a function, research worries it’s not being appreciated, because that has implications for job security.

In circumstances like these, submissive behaviors will not suffice: our job is to give people information in a way that makes their decisions better and more valuable. Letting others control how we do that job is not likely to highlight our unique value.

There’s a business lesson that researchers can learn from: in a free market, the strategy of cheapening your product to get more buyers is known as commoditization. It can technically earn you a living but it’s a hard life and it’s a road to the bottom, where your product is indistinguishable from others. The better approach is to provide outsized value even if the cost is high, but leave people feeling like it was a bargain. Excessive democratization practices commoditize the practice.

What would it look like if organizations saw research as a critical imperative, and a mistake to half-ass? What would research have to do differently than today to reach that future?